Making good decisions in chess is dependent upon an accurate evaluation of the position. Despite the many different criteria involved in the decision-making process, two stand out as pivotal: piece value and king safety. FM Weeramantry elaborates on these concepts and suggests that focusing on these alone can lead to success.

A good chess teacher is able to break down the complexities of chess into a simple, intelligible form. He must give his student a point of reference that remains constant. In this paper, I am proposing that less experienced players be advised to view the game only from the perspectives of value and king safety. It is my belief that this simplified approach helps the student understand what is going on and how to proceed.

The concept that embodies the very essence of chess is the concept of value. The conduct of the game should be viewed as a constant effort to increase the value of one’s position, on the premise that such improvement will lead the way to eventual victory. Too many inexperienced players throw all their resources into what they hope will be an irresistible mating attack without regard to the damage that such a strategy can inflict on the position as a whole. Perhaps an analogy with baseball will drive the point home more forcefully with our younger players. Everyone loves a home run. However, swinging for the fences on each turn at bat is definitely not in the best interests of the team. The situation on the field may call for a different strategy, for instance, a sacrifice bunt. A player who understands this is more valuable to his team.

Value can be understood and appreciated on several different levels. One of the first lessons a chess player learns is that each piece is assigned a point value: one for the pawn, three each for the knight and the bishop; five for the rook; and nine for the queen. This is the given or static value of a piece and generally serves as a guide to making trades, especially complex ones. Indeed, static value alone is sufficient to evaluate a position on a very basic level, by counting the total points for each side. This technique is particularly effective when teaching very young children because one of the first skills they are taught in school is to add numbers. More points mean more strength. More strength means a better position. As chess is, in reality, a struggle between two opposing forces, it is the stronger force that will prevail. The young player is suddenly empowered by being able to determine for himself who is in the winning position without constantly having to ask for outside assistance.

The next step is to understand that determining the true value of a piece involves considering not only its static value but its dynamic value as well. Dynamic value can be described as the function of a piece within a particular context. It can therefore be greater or lesser than the static value. Development and mobility are well explained in terms of value. Active pieces can easily exceed their static value, while undeveloped pieces clearly rank at the very bottom of the scale. I have found that an effective way of persuading a student to develop all his pieces is to walk by a game in progress and to pocket any undeveloped piece without uttering a word. The cries of indignation that inevitably follow this act of larceny on the part of the instructor provide an ideal opportunity to drive home an important lesson.

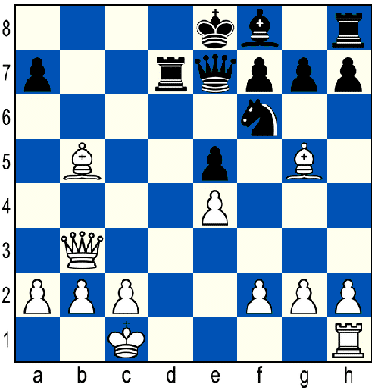

Let us now tum our attention to the following position from the illustrious “opera box” game brilliantly won by Paul Morphy.

A point count reveals that Black is ahead by three full points, a significant material advantage. In the hands of relatively inexperienced players, it is plausible that the material advantage will ultimately prevail, regardless of the position. However, when we factor in dynamic value, we realize that Black’s pieces may not be worth their full 30 points. The two undeveloped pieces, the rook on h8 and the bishop on f8, paint a sad picture of being confined to their quarters; and even two that have moved, the rook on d7 and the knight on f6, are both pinned. As White’s remaining rook is about to join the fray giving him full piece development, it is clear that his position is superior. Nevertheless, the attacker must maintain the initiative and not give his opponent the time to free his pieces. Morphy proved more than equal to the task. The game concluded in spectacular fashion: 14. Rd1 Qe6 15. Bxd7+ Nxd7 16. Qb8+! Nxb8 17. Rd8 mate.

I find that this particular game is an excellent illustration of the power of full development. It is an example of pure piece play where the pawns do not play a significant role. Indeed, the final position shows that the only White pawns that have moved are the two center pawns. The pawn’s primary function in the opening is to move out of the way of the bishop. Those who tend to push pawns indiscriminately should take note that Morphy completed his development while leaving six pawns behind on their original squares!

The fact that Morphy did not need the help of his pawns in launching his attack does not mean that pawns are best forgotten. Philidor once remarked that pawns are “the soul of chess”. Understanding principles of pawn play will enhance one’s handling of a position; and appreciating that some structures are better than others will assist the player in steering the game in the proper direction. But it is not necessary to place undue emphasis on this aspect of a position until one reaches a more advanced level of play. Suffice to know that a pawn mass has strength and that fractured pawn structures are weak.

Judging a position on the basis of value gives the student a well-defined strategy at all tunes: always strive to improve piece placement. To this, we should add one more directive: keep your king well protected.

When is the king safe? Many players, even experienced ones, believe that a king that is neatly tucked away in its castle behind three pawns on ceremonial duty is safe. But this could be only an illusion, one that is easily shattered by a few well-placed enemy pieces that are directing their attention towards that castled position. In reality, king safety is more a function of the enemy’s ability to attack than the extent of the pawn cover around one’s own king.

It is therefore necessary for a chess player to cultivate a sense of danger, not only for one’s own security but also for better appreciating the right moment to strike at one’s opponent. In this regard, I have found that the three questions formulated in the following checklist have been particularly effective with my students. They are:

1) Are there any open lines (ranks, files, diagonals) that the attacking pieces can use to invade the king’s sanctuary?

2) In the absence of existing lines of attack, can a line be forced open by a trade or a sacrifice?

3) Once a sacrifice is made, are there sufficient resources available to press on with the attack?

The destructive sacrifice, which strips the defending king of its protection, is without a doubt one of the more fascinating elements of chess. There are various such attacking patterns, for instance, the double bishop sacrifice introduced by Emmanuel Lasker. A recognizable sequence will often give a player the confidence necessary to initiate a combination. But how many players will consider a destructive sacrifice in unfamiliar situations? Material implies security and to most, that is a source of comfort. The drawback of this mindset is that one is too fearful even to consider the option of surrendering material. It is important then that, even when a player adopts the materialistic approach advocated earlier, he realize that there is one definite instance when material is of secondary importance, when the greater prize of the opposing king’s very life is at stake.

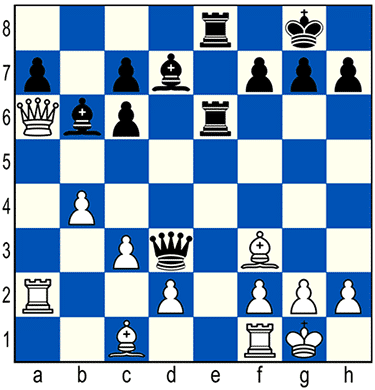

The greater the value of the piece sacrificed, the more spectacular the attack. One of the most inspiring sacrifices that I have seen is the queen sacrifice that Paul Morphy played against Louis Paulsen at the First American Chess Congress held in New York in 1857. Paulsen could not have been too happy with his position in the diagram below, but did he even remotely suspect the thunderbolt that Morphy was about to unleash? It is hard to imagine because it does not appear Black will have sufficient mating material after the impending queen sacrifice. It is a testament to the genius of Morphy that he was willing to explore this unlikely scenario and find a winning combination:

The game continued as follows: 17 …Qxf3!! 18. Gxf3 Rg6+ 19. Kh1 Bh3 20. Rd1 Bg2+ 21.Kg1 Bxf3+ 22.Kf1 Bg2+ 23.Kg1 Bh3+ 24.Kh1 Bxf2 25.Qf1 Bxf1 This is the only saving move. White has to surrender his queen in order to avoid 25…Bg2 mate. 26.Rxf1 Re2 27.Ra1 Rh6 28.d4 Be3 There is no practical way to prevent 29…Rxh2+ with a mating attack. 0-1.

The entire sequence of moves after the queen sacrifice is virtually forced. Such sequences are naturally easier to calculate as the opponent’s choices are limited. I would venture to say that, although very few players would have conceived of the queen sacrifice in the first place, even a player of more modest ability could well have analyzed its consequences correctly.

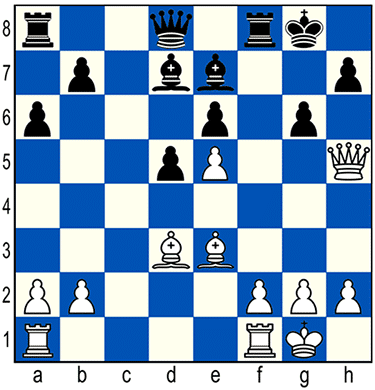

On the other hand, a sacrifice that does not trigger a forced sequence presents a more difficult call. Does the defender have sufficient time to bring over reinforcements to bolster the defense? Consider this position from a game that I played against Steve Anderson at the Westfield Chess Club in New Jersey.

This time, a destructive sacrifice on g6 suggests itself strongly. But how does White proceed after annihilating the pawn cover? I eventually came to the conclusion that I did have the time to bring a rook into the attack before my opponent reorganized his pieces defensively. Play continued as follows: 17. Bxg6 hxg6 18. Qxg6+ Kh8 19.Rad1 Rf5 20. Qh6+ Kg8 21. Rd4 Resigns. The intermediate check on h6 made it clear that Black would not be able to block White’s intended rook check successfully. Moreover, an attempt to create an escape square on e7 by playing 21 … Bf8 would fail to 22. Rg4+ Kf7 23. Qg6+ Ke7 24. Bc5 mate. Thus, there are several steps to be followed in executing a destructive sacrifice: finding a way to break through, calculating the details of the operation and, when a sequence is not forced, assessing the likelihood of success.

One of the great difficulties of chess is that it is a game of shifting priorities. The key to this simplified approach is that the concepts of value and king safety remain constant as barometers in judging a position and the right answer will be found most times.

Note: For a deeper analysis of these games, see Great Moves: Learning Chess Through History. The Paulsen-Morphy game is also featured in Best Lessons of a Chess Coach – Extended Edition.

The National Scholastic Chess Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit educational organization. Donations are tax-deductible. Relevant IRS information is available on request.